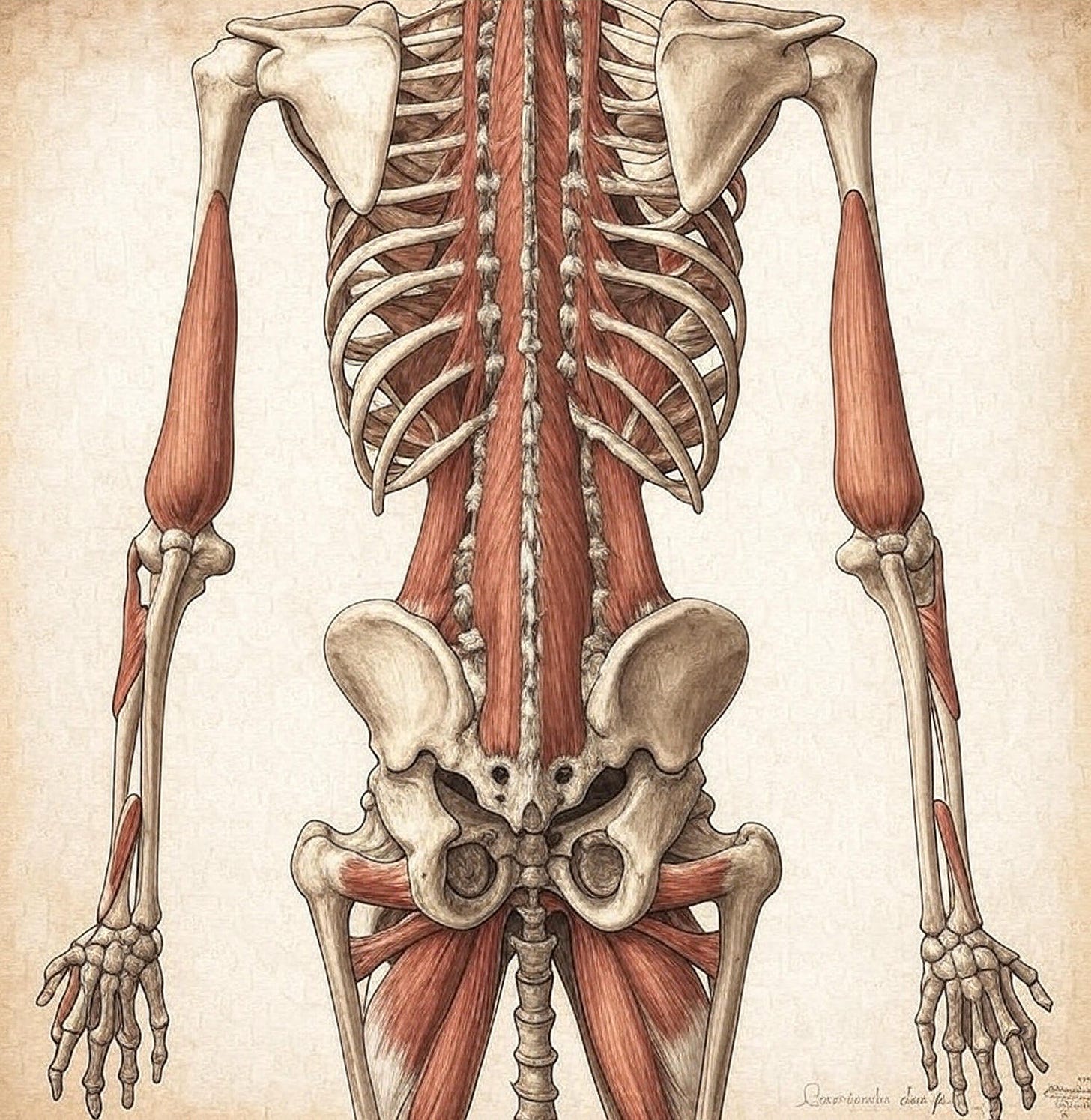

It’s no shock to say we’re all aging, slowing down, and losing flexibility as time passes. The lumbar spine, part of the low back, is often where this decline first shows up. Built to handle forces like gravity or a lifted load, the lumbar spine spreads that stress across the body. Its surrounding muscles stabilize the bones and ligaments, whether we’re standing still or on the move. Over a lifetime, this takes a toll, leaving the low back stiffer and prone to pain that can range from a nagging ache to something crippling. A totally pain-free low back might be a stretch, but one that’s only occasionally achy is within reach. The trick is to first boost the isometric strength of the musculature and mobility of the lumbar vertebral joints, then shift to more dynamic strengthening exercises.

Why do we lose strength and mobility in our lumbar spine? Each lumbar vertebra is separated by a lumbar disc, which acts as both a “shock absorber” and a spacer between the vertebrae. As we age, these discs lose height, bringing the vertebrae closer together. This often reduces the lumbar spine’s natural forward curve (lordosis), limiting flexion (forward bending) range of motion, though compensation elsewhere—like in the hips or upper spine—can exaggerate lordosis. Both the loss and compensatory increase in this curve shift stability to the bones and ligaments, letting the muscles that control spinal motion atrophy further. This altered curvature, whether flattened or overcorrected, restricts movement between the lumbar vertebrae and may even lead to natural fusion in the lower lumbar spine. While disc degeneration is an unavoidable part of aging, its effects can be slowed, and spinal strength and mobility can be preserved or enhanced through targeted efforts.

The ubiquitous prescription for low back pain is core strengthening, and this remedy is not without merit. Our vertebrae are designed to move both as a unit and relative to each other. Accordingly, the core strengthening approach likens the spinal muscles to a metaphorical “brace,” stabilizing the vertebrae and limiting excessive motion in the low back during stress. To develop this “brace,” I do not recommend a bunch of sit-ups, at least not when starting out. The core musculature spends most of its time supporting our torsos in static positions—standing, sitting, or rotating slightly while walking. In these situations, the musculature is stabilizing in response to small movements. Exercises like planks or the hollow position are excellent to start with.

Hollow Position

For the hollow position, lie on your back with your knees bent, abdominals contracted, and low back pressed flat against the floor. Extend your arms straight up to lift your shoulder blades off the ground, then raise your feet a few inches off the floor. Hold this position for about 30 seconds, ensuring your low back doesn’t arch upward. To make it harder, keep your shoulder blades lifted while lowering your arms gradually behind your head. You can also straighten your legs and lower them closer to the floor. The key is maintaining a strong abdominal contraction to keep your low back flat on the ground.

Plank

The plank is another isometric core exercise, but you start by lying face down. Prop yourself up on your elbows and toes, then adjust your hips so your body forms a straight line, engaging your abdominals to keep your low back neutral or slightly rounded. As with the previous exercise, start with a few sets of 30-second holds.

While a strong core is essential for back health, a mobile lumbar spine preserves range of motion and supports core strength during everyday movements. I find two invaluable movements—wall-assisted lumbar flexion for bending and 90/90 rotations for twisting—to be especially effective.

Wall-Assisted Lumbar Flexion

For this stretch, stand about a foot from a wall and lean your back against it. Slide down until your knees bend at a 45-degree angle. Slowly reach toward the ground, peeling your upper back off the wall. Engage your abdominals by sucking your belly button toward your spine, bending at the lumbar spine. Keep bending until you feel a stretch in your low back, then hold for about 30 seconds. Repeat, noticing tight spots in your low back, and try reaching slightly to one side or the other to target muscles on either side of your spine.

90/90 Rotations

Sit on the ground with your left knee bent at a 90-degree angle in front of you, the outside of your left thigh flat on the floor. Bend your right knee at 90 degrees, positioning it out to your right side, with the inside of your right thigh on the ground. Gently twist your spine left, reaching across your left thigh toward the ground with both hands, and hold for 30 seconds. Then switch so your right knee is in front and your left knee is out to the side. Rotate your spine right, reaching across your right thigh, and hold for 30 seconds.

Conclusion

Aging may inevitably challenge the lumbar spine, but it doesn’t have to dictate our quality of life. The gradual stiffening and discomfort that creep into the low back can be met with proactive steps—building a resilient core and preserving lumbar mobility. Exercises like the hollow position and planks lay a foundation of isometric strength, turning the spinal musculature into that vital “brace” against daily stresses. Meanwhile, stretches like wall-assisted lumbar flexion and 90/90 rotations keep the spine supple, countering the rigidity that comes with disc degeneration and compensatory shifts. Together, these approaches address both the symptoms and the root causes of lumbar decline, offering a balanced strategy to manage pain and maintain function. Scientific evidence backs this dual focus: core strength reduces strain on the spine, while mobility work slows the loss of range of motion. The beauty of this plan lies in its simplicity and adaptability—starting with 30-second holds or gentle stretches, anyone can tailor it to their current ability and progress over time. No one escapes aging, but with consistent effort, the lumbar spine can remain a source of strength rather than a limiter. An occasionally achy low back isn’t just a dream—it’s an achievable reality, one plank, stretch, and rotation at a time.