The Core and The Psoas

The body’s center of gravity is in an anatomical region, known as the “core cylinder,” a functional structure that supports stability and movement. The psoas, a muscle that has entered the zeitgeist as of late, is the linchpin of this system. The diaphragm forms the top of the cylinder, contracting and relaxing to manage thoracic and abdominal pressure. The pelvic floor creates the bottom, engaging to maintain balance, both in standing and while moving. The front consists of the transversus abdominis and obliques, contracting to brace the abdomen. The rear is supported by the psoas, connecting the lumbar spine, its musculature and the femur. Together, these components function as the body’s core. While the psoas is one of many muscles in this system, it is the muscle that can effect the most change when the cylinder becomes dysfunctional.

Diaphragm and Psoas

Dysfunction in the core cylinder is the breakdown or alteration in the interaction of these muscle groups, often affecting the underlying function they serve. As an example, a tight psoas pulls the lumbar spine into hyperlordosis (an extreme forward curve), tilting the pelvis anteriorly. This shortens the length of the diaphragm, potentially restricting its full excursion during breathing. The compromised breathing caused by the tight psoas and shortened diaphragm, will lead to subtle or not-so-subtle changes to our nervous system. Check in with your breathing when you are angry; it will not be slow, deep, and controlled. Rather, when we are stressed our breathing is shallow and rapid. Here, our nervous system state or mood is influencing our breath. This breathing pattern is perfect for exhaling a lot of CO2, relative to inhaling O2, putting our bodies in a physiologic state called hypocapnia — fight or flight. However, breathing can be the tail that wags the dog in that the speed and depth at which you breathe will influence your mood. Habitual shallow breathing brought on by the altered morphology of a short psoas can put you into flight or fight, without the external stimulus of an angry boss, hostile email or seeing a mountain lion. Our tight psoas has us teed-up and ready to pounce, or perhaps just a bit less relaxed than we could be.

Psoas and Pelvic Floor

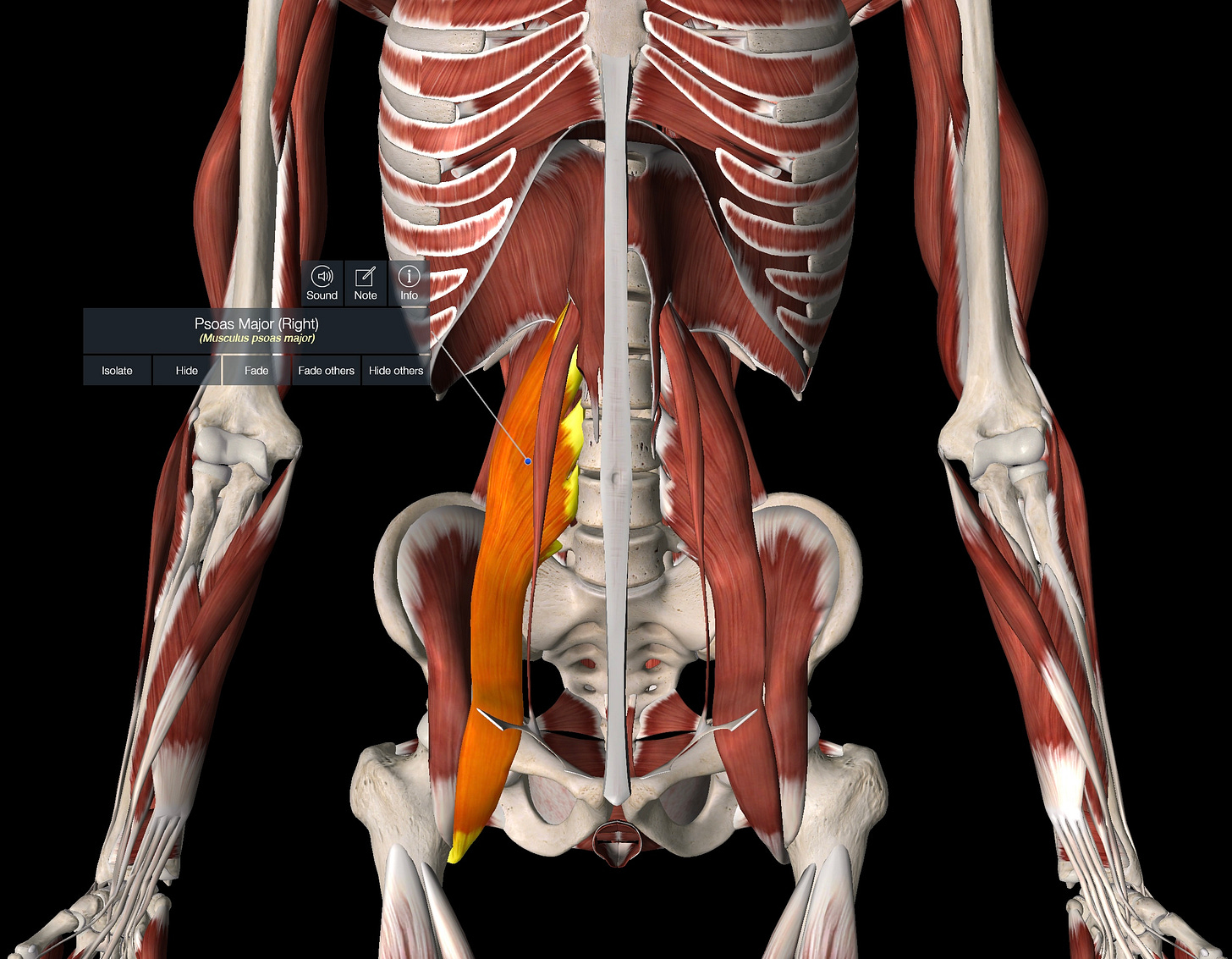

The psoas major originates from the lumbar spine (T12-L5) and courses downward through the pelvis to insert on the femur. The pelvic floor, a multilayered sling of muscles, spans the pelvic outlet, attaching to the coccyx, sacrum, and pelvic bones. Though the psoas and the pelvic floor don’t share direct bony attachments, they do share fascial connections. The psoas is wrapped in the psoas fascia, which connects with the endopelvic fascia creating a continuum of connective tissue. This fascial web means that tension or laxity in the psoas can ripple downward to the pelvic floor, and vice versa.

A functional relationship between the psoas and the pelvic floor is essential to moving, be it walking or running. When we use our psoas to lift our leg to take a step forward, backward or to the side, the pelvic floor must contract on the opposite side to stabilize the hip for the leg that is planted on the ground. The relative strength of the contractions of the psoas and the pelvic floor will mirror each other, as a weak pelvic floor contraction will limit the power of the psoas. Conversely, a tight psoas will not be able to contract to its fullest potential, limiting the stabilizing response from the pelvic floor.

The Psoas and Back Pain

The psoas and lumbar spine musculature have a reciprocal and interdependent relationship. The psoas pulls the spine and hips forward as a flexor, while the lumbar spine muscles counteract this by extending, stabilizing, and laterally flexing the spine. Their shared attachments on the lumbar spine and fascial connections mean they’re constantly influencing each other, balancing mobility and stability. Dysfunction in one negatively affect to the other, making their harmony essential for a pain-free, functional lower back and pelvis.

When a patient walks through my door with back pain, I start by releasing the psoas. While self-manipulating the psoas at home is challenging, it is not impossible.

Down-Regulation

If you are in acute severe pain, you have to start by calming your nervous system. Lay on your back with your hips and knees bent at 90 degrees, calves resting on the seat of your couch or an object of similar height. Gently engage your abdominals, tilting your pelvis backwards such that your low back is pressed into the floor. Nod your chin down a bit or support your head with a small pillow. Keeping a gentle contraction in your abdominals, slowly inhale through your nose for 3-5 seconds. Pause briefly at the top of the inhale, then begin to slowly exhale through your nose. This is the important - exhale for longer than you inhaled, twice as long if possible, 6-10 seconds. Find a rhythm that is not stressful and continue this until your acute pain has subsided completely or diminished to a point that is tolerable.

Psoas Release

If your back pain is not severe, but has been bothering you for a few days to a few years, you may need to physically release the psoas. You will need a ball, about the size of a softball, but preferably not has hard. The area you want to apply the pressure to is on the diagonal half-way between your belly button, and the boney protuberance at the front of your hip (the ASIS - anterior superior iliac spine). Place the ball on the ground and lay on it, centering the ball over this area. Gently lower yourself onto the ball and begin some long, slow inhales and exhales - slowly sinking onto the ball with each exhale. You want to build up to a tolerance of at least a minute, maybe two. Repeat this daily, unless the area begins to feel a bit sore, then you may want to try it every other day or two.

Stretch of the Psoas

Lower yourself to the ground in a lunge position - one knee on the ground with the opposite foot out in front of you. At this point you may already feel a stretch in the front of the waist and/or thigh. Contract your abdominals to increase the intensity of the stretch. If you don’t feel much of a stretch at this point, shift your pelvis forward without leaning forward from the shoulders. Hold this stretch for at least a minute, a few times a day.

The psoas, though just one muscle in the core cylinder, profoundly influences whole-body function. Its relationships with the diaphragm, pelvic floor, and spine demonstrate why addressing a tight psoas yields far-reaching benefits. Beyond biomechanics, this muscle affects breathing patterns, stress responses, and pain perception. The down-regulation, manual release, and stretching techniques offered provide practical pathways to restore proper function.