The Teenage Athletic Knee

High school athletes are very active people. In season, it is common for these athletes to have intense practices and competitions 5 to 6 days per week. Many high schoolers are multi-sport athletes without any extended off-season for their growing musculoskeletal systems to rest and recharge. Layering on top of this schedule club sports and off-season training, it is no wonder that I see this population in my office for knee pain. Most of the knee pain these teenagers suffer is not from acute injuries like ACL or meniscus tears, but an overuse injury called Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome. This syndrome is a fancy way of describing a collection of symptoms that are the result of irritation of the cartilage underneath the patella (kneecap). While this pain can be intense and debilitating, it is treatable, and I can usually get the athlete back to their sport without missing much of their season, if any.

Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome is characterized by moderate to severe pain surrounding the patella (kneecap). This pain becomes apparent with movements like descending stairs or decelerating from a sprint, but the pain can also become apparent after intense activity, once adrenaline starts to wear off. The pain is often severe, albeit disproportionate to the actual injury. This injury can often interfere with basic functional activities like navigating stairs, prolonged sitting and short walks.

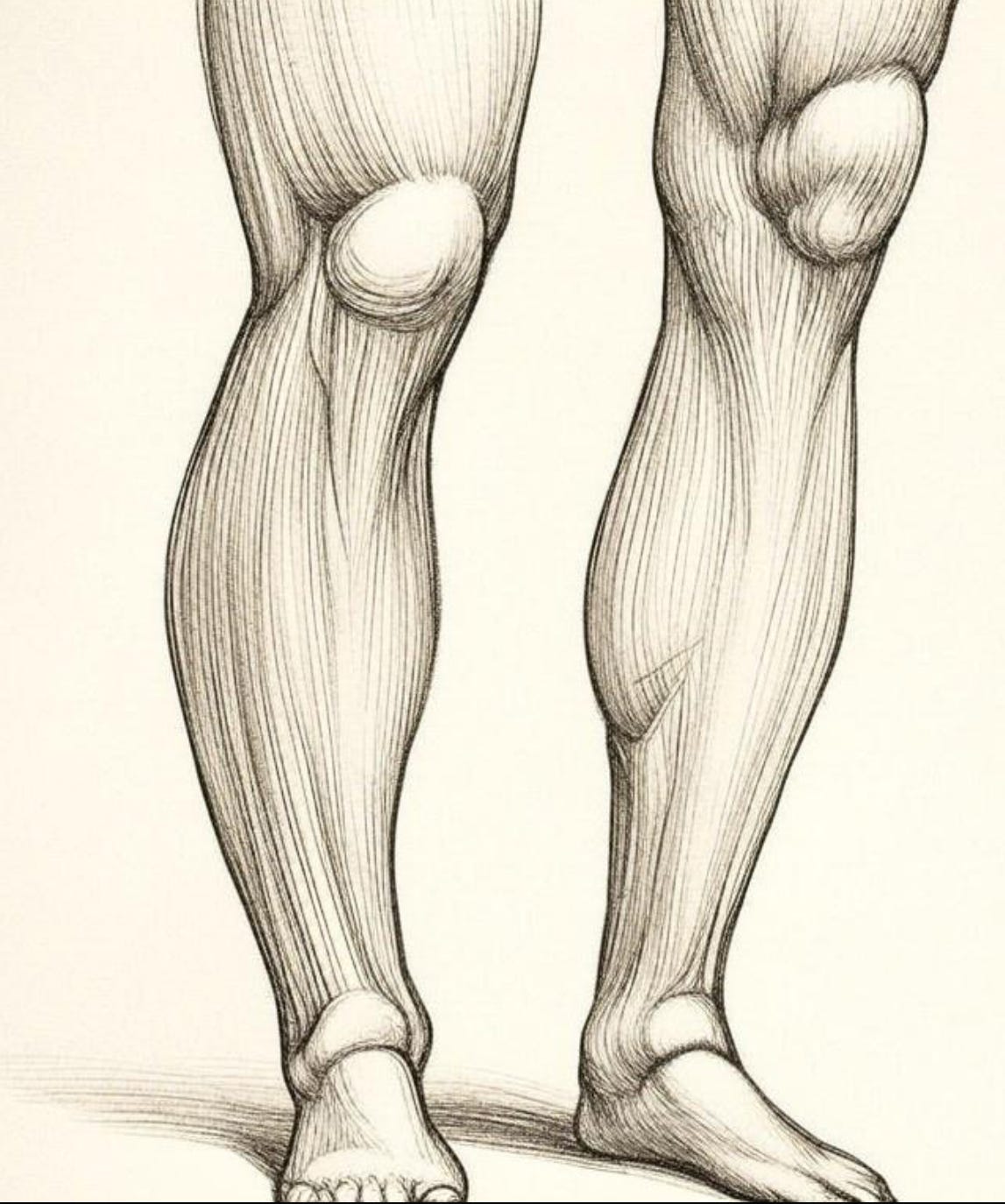

The dysfunction and pain associated with this injury is due to an irritation of the cartilage under the kneecap resulting from a dynamic misalignment of the patella relative to the femur. When our knee is straight, our patella sits in front of the bottom femur. As we bend our knee, the patella slides down in the trochlear groove until it is sitting at the very end of the femur. The problems begin when the patella begins to repeatedly move outside the trochlear groove, irritating the cartilage underneath the patella. Subsequent movements compelling us to bend the knee, which is in most things we do, further irritates the already angry tissue.

While adults also suffer from Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome, teens tend to suffer from this ailment for a different reason—they are still growing. Growth spurts in the teenage years are characterized by relatively fast growth in the epiphyseal plates (growth plates) of the femur (thigh) and the tibia (shin). These plates are layers of rapidly dividing cartilage cells that can remain active up to 19 years old—even longer in some late bloomers.

In the context of the knee, these epiphyseal plates ultimately determine the length of the femur and the tibia, and it is the job of the slower growing musculature and connective tissue to play catch-up to these growing bones. This mismatch in growth between the bones and muscles can cause a dynamic misalignment of the patella for two reasons.

One, the rapid bone growth of the femur and tibia leads to excessive tension in the quadriceps muscle and tendon as its growth struggles to keep up with that of the bones. It is this excessive tension that can pull the patella slightly out of its anatomical groove, causing it to bump into the ends of the femur. Two, the musculature upstream at the hips struggles to stabilize the fast-growing femur and tibia. For example, when a soccer player plants their foot to kick a ball, the hip of the corresponding planted foot deviates too far to the side, creating an excessive lateral angle of pull on the patella. Again, the patella is pulled slightly out of its groove. Once the patella starts to deviate from its natural path, the cartilage under the kneecap becomes irritated, starting a painful inflammatory cascade.

Rest and ice can help temporarily reduce or eliminate the pain associated with Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome, but the condition inevitably comes back as these athletes are still active and growing. The remedy is twofold: remove the excessive tension from the quadriceps muscle and tendon while you strengthen the quadriceps and hip musculature.

Hands-on myofascial release by a trained clinician is generally required. This precise manual therapy is needed to remove tension from the muscle bellies of the four muscles comprising the quadriceps and contractures that have formed in the quadriceps tendon. Using a foam roller or lacrosse ball to relieve tension in this muscle group can be helpful in maintaining its extensibility between physical therapy sessions, but these tools are often inadequate as a standalone treatment. Furthermore, I generally discourage frequent and strong stretching while the knees are inflamed. Repeated or strong stretching pulls the patella into the end of the femur, further exacerbating the inflammation of the patellar cartilage.

Progressive resistance training of the quadriceps and hip musculature is also required to treat this condition. Initially it may be necessary to strengthen the relevant musculature without bending the knees. But in all cases, exercises should start in an “openchain” orientation. That is to say, the musculature of the hip and thigh should initially be trained while the foot is off the ground. The open-chain position allows for the musculature to be strengthened without ground reaction forces compelling those muscles to pull the patella off track. These exercises should be focused on musculature that abducts the hip - pulls the hip away from the midline of the body. Strengthening the glutes with abduction based exercises serves to provide stability to the hip when the athlete plants the foot to kick, throw, etc.

After a couple of weeks, therapeutic exercises can be progressed to a “closed-chain” orientation with both feet on the ground. At this stage, having both feet on the ground will help keep the knees stay lined up under the hips, ensuring a line of pull on the patella that encourages it to stay in its groove. From here, I progress the athlete to closed-chain exercises on one foot to strengthen the hip musculature and quadriceps in more sport-specific movements.

With Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome, I do not recommend knee braces as they can often make the situation worse if they adversely influence the tracking of the patella. Additionally, as with most of the conditions I treat, I don’t like the use of modalities like ultrasound, or any of the electrotherapeutic modalities (TENS, NMES, Russian stimulation) as their benefit is transitory at best.

When a teenage athlete with Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome can return to their sport depends on the individual and how irritated the knees are when starting treatment. While it is not ideal for the healing process, I can often treat the athlete with little to no time off at all. However, it is important to be realistic about the cost-benefit of continuing to play one’s sport while injured. That said, a proper balance of treatment and sport is almost always arrived at with a conversation between myself, the athlete and their parents.